| THINK-ISRAEL |

| HOME | November-December 2009 Featured Stories | Background Information | News On The Web |

The British who were given the Mandate by the League of Nations to aid the Jews in establishing a Jewish State reneged and during the 1930's as the Nazis were systematically hunting and exterminating Jews in Europe, they closed Jewish immigration to Palestine. After the War, they continued to refuse the Jewish survivors entry. With the pressure of needing a state for the survivors of the Holocaust, Israel was willing to take a limited part of the land it owned according to International Law. Resolution 181 was adopted by the General Assembly November 29, 1947. The Resolution was rejected by the Arabs and It became null and void when the Arab states invaded the new-born state of Israel in 1948. It was never adopted by the Security Council, so it was never a binding resolution.

In 1947 the British put the future of western Palestine into the hands of the United Nations, the successor organization to the League of Nations which had established the Mandate for Palestine. A UN Commission recommended partitioning what was left of the original Mandate — western Palestine, into two new states, one Jewish and one Arab. Jerusalem and its surrounding villages were to be temporarily classified as an international zone belonging to neither polity.

What resulted was Resolution 181, a non-binding recommendation to partition Palestine [Eretz Israel], whose implementation hinged on acceptance by both parties — Arabs and Jews. The resolution was adopted on November 29, 1947 in the General Assembly by a vote of 33 to 12, with 10 abstentions. Among the supporters were the United States and the Soviet Union as well as other nations including France and Australia. The Arab nations, including Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, denounced the plan on the General Assembly floor and voted as a bloc against Resolution 181 promising to defy its implementation by force [italics by author].

The resolution recognized the need for immediate Jewish statehood (and a parallel Arab state), but the 'blueprint' for peace became a moot issue when the Arabs refused to accept it. Subsequently, de facto realities on the ground in the wake of Arab aggression (and Israel's survival) became the basis for UN efforts to bring peace. Resolution 181 lost its validity and relevance.

Aware of Arabs' past aggression, Resolution 181, in paragraph C, calls on the Security Council to:

"... determine as a threat to the peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression, in accordance with Article 39 of the Charter, any attempt to alter by force the settlement envisaged by this resolution." [italics by author]

The ones who sought to alter by force the settlement envisioned in Resolution 181 were the Arabs who threatened bloodshed if the UN were to adopt the Resolution:

"The [British] Government of Palestine fear that strife in Palestine will be greatly intensified when the Mandate is terminated, and that the international status of the United Nations Commission will mean little or nothing to the Arabs in Palestine, to whom the killing of Jews now transcends all other considerations. Thus, the Commission will be faced with the problem of how to avert certain bloodshed on a very much wider scale than prevails at present. ... The Arabs have made it quite clear and have told the Palestine government that they do not propose to co-operate or to assist the Commission, and that, far from it, they propose to attack and impede its work in every possible way. We have no reason to suppose that they do not mean what they say." [italics by author]

Arabs' intentions and deeds did not fare better after Resolution 181 was adopted:

"Taking into consideration that the Provisional Government of Israel has indicated its acceptance in principle of a prolongation of the truce in Palestine; that the States members of the Arab League have rejected successive appeals of the United Nations Mediator, and of the Security Council in its resolution 53 (1948) of 7 July 1948, for the prolongation of the truce in Palestine; and that there has consequently developed a renewal of hostilities in Palestine."

The conclusion:

" ... Having constituted a Special Committee and instructed it to investigate all questions and issues relevant to the problem of Palestine, and to prepare proposals for the solution of the problem, and Having received and examined the report of the Special Committee (document A/364). ... Recommends to the United Kingdom, as the mandatory Power for Palestine, and to all other Members of the United Nations the adoption and implementation, with regard to the future Government of Palestine, of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union set out below; ... " [italics by author].

ISRAEL'S INDEPENDENCE IS NOT A RESULT OF A PARTIAL IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PARTITION PLAN.

Resolution 181 has no legal ramifications — that is, Resolution 181 recognized the Jewish right to statehood, but its validity as a potentially legal and binding document was never consummated. Like the proposals that preceded it, Resolution 181's validity hinged on acceptance by both parties of the General Assembly's recommendation.

Cambridge Professor Sir Elihu Lauterpacht, Judge ad hoc of the International Court of Justice, a renowned expert on international law and editor of one of the 'bibles' of international law, Oppenheim's International Law, clarified that from a legal standpoint, the 1947 UN Partition Resolution had no legislative character to vest territorial rights in either Jews or Arabs. In a monograph relating to one of the most complex aspects of the territorial issue, the status of Jerusalem, Judge, Sir Lauterpacht wrote that any binding force the Partition Plan would have had to arise from the principle pacta sunt servanda, that is, from agreement of the parties at variance to the proposed plan. In the case of Israel, Judge Sir Lauterpacht explains:

"... the coming into existence of Israel does not depend legally upon the Resolution. The right of a State to exist flows from its factual existence - especially when that existence is prolonged, shows every sign of continuance and is recognised by the generality of nations."

Reviewing Lauterpacht's arguments, Professor Stone, a distinguished authority on the Law of Nations, added that Israel's "legitimacy" or the "legal foundation" for its birth does not reside with the United Nations' Partition Plan, which as a consequence of Arab actions became a dead issue. Professor Stone concluded:

"... The State of Israel is thus not legally derived from the partition plan, but rests (as do most other states in the world) on assertion of independence by its people and government, on the vindication of that independence by arms against assault by other states, and on the establishment of orderly government within territory under its stable control."

By the time armistice agreements were reached in 1949 between Israel and its immediate Arab neighbors (Egypt, Lebanon, Syria and Trans-Jordan) with the assistance of UN mediator Dr. Ralph Bunche - Resolution 181 had become irrelevant, and the armistice agreements addressed new realities created by the war. Over subsequent years, the UN simply abandoned the recommendations contained in Resolution 181, as its ideas were drained of all relevance by events. Moreover, the Arabs continued to reject 181 after the war when they themselves controlled the West Bank (1948-1967) which Jordan invaded in the course of the war and annexed illegally.

Professor Stone wrote about this 'novelty of resurrection' in 1981 when he analyzed a similar attempt by pro-Palestinians 'experts' at the UN to rewrite the history of the conflict. Stone called it "revival of the dead."

Resolution 181 had been tossed into the waste bin of history, along with the Partition Plans that preceded it.

To view an entire article on this, including the recommended map and all footnotes, please click here.

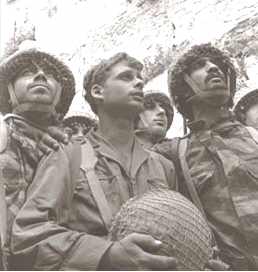

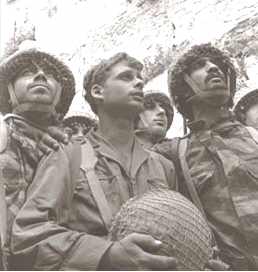

In May 1967, Egypt moved its forces into the Sinai desert and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. When diplomatic manoeuvring by the U.S.A, Israel and the U.N. produced no relief, Israel struck preemptively and beat the combined armies of Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Syria in six days, with no material support from the U.S.A. It took control of Samaria, Judea, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights and the Sinai Peninsula. An armistice was declared and the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 242, which called on Israel to relinquish some unspecified part of the territory it had conquered, providing the arabs signed on to allow Israel to live in peace, free from the threat of armed aggression. Israel was not urged to return to the armistice lines of 1967. Israel signed a peace treaty with Egypt and returned to them the entire Sinai Peninsula. It is ironic that the pro-Arab faction now (a) insists 242 gives the rights to Samaria and Judea and the Gaza strip to the Palestinian Arabs, who are not even mentioned in the document; and (b) insists Israel return to the 1967 Armistice lines, which the Arabs rejected at the time.

Resolution 242 is the cornerstone for what it calls "a just and lasting peace." It calls for a negotiated solution based on "secure and recognized boundaries" — recognizing the flaws in Israel's previous temporary borders — the 1948 Armistice lines or the "Green Line" — by not calling upon Israel to withdraw from 'all occupied territories,' but rather "from territories occupied."

The United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 242 in 1967 following the Six-Day War. It followed Israel's takeover of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. The resolution was to become the foundation for future peace negotiations. Yet contrary to Arab contentions, a careful examination of the resolution will show that it does not require Israel to return to the June 4, 1967 Armistice lines or "Green Line."

Resolution 242 was approved on November 22, 1967, more than five months after the war. Although Israel launched a pre-emptive and surprise strike at Egypt on June 5, 1967, this was a response to months of belligerent declarations and actions by its Arab neighbors that triggered the war: 465,000 enemy troops, more than 2,880 tanks and 810 aircrafts, preparing for war, surrounded Israel in the weeks leading up to June 5, 1967. In addition, Egypt had imposed an illegal blockade against Israeli shipping by closing the Straits of Tiran, the Israeli outlet to the Red Sea and Israel's only supply route to Asia — an act of aggression — in total violation of international law. In legal parlance, those hostile acts are recognized by the Law of Nations as a casus belli [Latin: Justification for acts of war].

The Arab measures went beyond mere power projection. Arab states did not plan merely to attack Israel to dominate it or grab territory; their objective was to destroy Israel. Their own words leave no doubt as to this intention. The Arabs meant to annihilate a neighboring state and fellow member of the UN by force of arms:

THE MEANING OF THE WORDS "ALL" & "THE"

The UN adopted Resolution 242 in late November 1967, five months after the Six-Day War ended. It took that long because intense and deliberate negotiations were needed to carefully craft a document that met the Arabs' demand for a return of land, and Israel's requirement that the Arabs recognize Israel's legitimacy, to make a lasting peace. It also took that long because each word in the resolution was deliberately chosen, and certain words were deliberately omitted, according to negotiators who drafted the resolution.

So although Arab officials claim Resolution 242 requires Israel to withdraw from all territory it captured in June 1967, nowhere in the resolution is that demand delineated. Nor did those involved in the negotiations and drafting of the resolution want such a requirement. Instead, they say Resolution 242 explicitly and intentionally omitted the terms 'the territories' or 'all territories.' The wording of UN Resolution 242 clearly reflects the contention that none of the territories were occupied territories taken by force in an unjust war.

Because the Arabs were clearly the aggressors, nowhere in UN Security Council Resolutions 242 is Israel branded as an invader or unlawful occupier of the territories. The wording of UN Resolution 242 clearly reflects the contention that none of the territories were occupied territories taken by force in an unjust war.

Given that the Palestinian arabs never had soverignty over the West Bank and East Jerusalem and Jordan had seized them illegally in 1948, Professor, Judge Stephen M. Schwebel, former President of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague, concluded:

"State [Israel] acting in lawful exercise of its right of self-defense may seize and occupy foreign territory as long as such seizure and occupation are necessary to its self-defense. ... Where the prior holder [Jordan] of territory had seized that territory unlawfully, the state which subsequently takes that territory in the lawful exercise of self-defense [Israel] has, against that prior holder, better title."As between Israel, reacting defensively in 1948 and 1967, on the one hand, and her Arab neighbors, acting aggressively, in 1948 and 1967, on the other, Israel has the better title in the territory of what was Palestine, including the whole of Jerusalem, than do Jordan and Egypt."

(http://www.2nd-thoughts.org/id248.html. See also id162 and id91)

Professor Julius Stone, a leading authority on the Law of Nations, has concurred, further clarifying:

"Territorial Rights Under International Law. ... By their [Arab countries] armed attacks against the State of Israel in 1948, 1967, and 1973, and by various acts of belligerency throughout this period, these Arab states flouted their basic obligations as United Nations members to refrain from threat or use of force against Israel's territorial integrity and political independence. These acts were in flagrant violation inter alia of Article 2(4) and paragraphs (1), (2), and (3) of the same article."

If the West Bank and Gaza were indeed occupied territory — belonging to someone else and unjustly seized by force — there could be no grounds for negotiating new borders.

To view an entire article on this,

please click here.

Eli E. Hertz is president of Myths and Facts, Inc. The

organization's objective is to provide policymakers, national

leadership, the media and the public-at-large with information and

viewpoints that are founded on factual and reliable content. Contact

him at today@mythsandfacts.org and visit the website:

http://www.mythsandfacts.org/

| HOME | November-December 2009 Featured Stories | Background Information | News On The Web |