MOVING BEYOND IMPASSE IN CLIMATE CHANGE COMMUNICATIONS

by Katie L. Burke, October 26, 2016

If you're considering how to write for, speak to, or have conversations with those who may be resistant to the idea that climate change is happening and is caused by human activities, here is an overview of communication ideas that the climate change literature has explored so far.

Several weeks ago, Pew Research came out with new poll data[1] on climate change and public trust. Although it didn't really tell us much that the literature hadn't already indicated about climate change and science communication, the new data do provide a great overview of what is known, back up some earlier studies, and flesh out some details. The data show that whether and how much people believe that climate change is caused by human activities remains polarized and is based on political inclinations, something we've known for years. In other words, what one thinks about climate science is based on one's politics rather than on scientific knowledge. The literature has indicated for years, and the Pew poll reiterates, that liberals place a higher level of trust in climate scientists than conservatives do.

When discussing how to deal with misinformation about science, especially around polarizing topics, I often hear people say it's a lost cause to try to change minds. But this thinking misses the point that even when it comes to an issue like climate change, many people[2] (about 34 percent) are unsure what to think. In fact, those concerned about anthropogenic climate change far outnumber those who doubt its causes. So perhaps what science communicators need to do is to stop trying to change minds and instead focus on shared concerns and values. As people process new information, they decide whether they believe it based on[3] cultural cues that signal trustworthiness and shared values. Unless one understands where a person's mistrust is coming from—for example, why some people do not believe climate scientists—a space for discourse is unlikely to emerge and a shared sense of understanding and trust is unlikely to grow.

Obviously, no magic wording is going to make an audience reverse their stance on a topic, but there is plenty of research to indicate potential approaches to having a productive discussion. Of course, science communication scholars debate about the best strategy for persuading audiences resistant to the idea of human-induced climate change. Nevertheless, delving into the science communication literature has helped me have less hostile and more thoughtful interactions with readers, audiences, students, community members, and family when I communicate about climate change. Not all of the study results and communications strategies I'm going to discuss below apply to every audience. They come from studies with limited sample sizes—just a small set of people—and like any communication strategy, is never guaranteed to work. I urge you, however, to give them a try.

One caveat: Ideally, any climate change communication would be tested out with focus groups before going big. But many people put in positions of speaking, writing, or teaching about climate change don't have focus-group testing at their disposal and could benefit from an overview of what the literature says. Even if you're working on an article for a large media venue or speaking at a public event, practicing on a few people who reflect your potential audience or your worst critics could be a great learning experience. And the more one can seek information from an audience about their concerns, the better.

So if you're considering how to write for, speak to, or have conversations with those who may be resistant to the idea that climate change is happening and is caused by human activities, here is an overview of communication ideas that the climate change literature has explored so far:

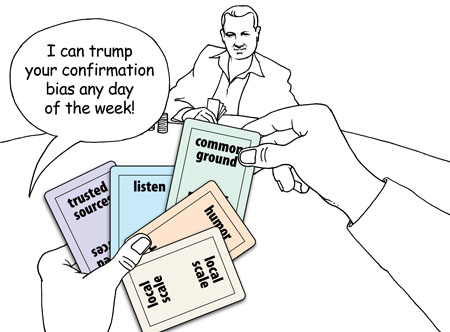

1. Establish common ground with the audience first.

Starting in a place where everyone can agree will make an audience more likely to listen, rather than seeing the author or speaker as someone who is part of an opposing group that is unsympathetic to their values. Given the state of today's online discourse and political debates, it may be surprising that people, regardless of political affinity, agree on quite a lot of things. What common ground do liberals and conservatives have around this issue? Interestingly, most Americans do agree about some of the solutions to climate change, even if they don't agree on the nature of the problem it could solve. Most people[4] support increasing renewable energy use and decreasing dependency on fossil fuels, for example. And the new Pew Research data show that both liberals and conservatives spend an equal amount of time outdoors and want to protect their environment, even if they do not identify with the most common ways climate change has been framed in the past.

2. Frame the issue in ways that speak to your audience's concerns.

Climate change has been framed time and again in a way that tends to speak only to environmental values and the need for a person or a country to change their behavior. But climate change is not just going to affect the environment. It is going to change everything: the economy, jobs, public health. Protecting the status quo and the values of the past is generally important to conservatives. Framing climate change as something that must be stopped to protect the country we know and love can work much better[5] than telling people that their way of life is a problem. In addition, framing the issue around public health problems that climate change will exacerbate has been shown[6] to be more effective than framing the topic around environmental values. And framing it around the promise of technology to address climate change is also more palatable[7] to conservative audiences, although some researchers have noted that this approach should be taken with caution, because some technologies, such as geoengineering, are unlikely to be developed until it's too late.

3. Point out personal experiences of the effects of climate change.

It's hard to deny something when you see it happening, and indeed studies indicate[8] that showing real effects of climate change on people with whom the audience can relate is effective for raising their engagement with the issue.

4. Avoid using the terms climate change and global warming up front, or avoid them completely if it's possible.

Even scientific terms can become infused with cultural meanings if they have been framed repeatedly in certain ways. When a word has been used to repeatedly demonize a group, it becomes kind of like Voldemort from Harry Potter: It cannot be named without inducing the feelings associated with it. Unfortunately, the term climate change is branded as a liberal talking point. Using climate change can in turn brand a speaker or author in this way. Indeed, this happened[9] to Republican congressman Bob Inglis when he decided the issue of climate change was too important to ignore. However, talking about solutions to climate change—such as renewable energy use—while speaking to conservative values can build trust without bringing up the polarizing force of Voldemort. Conservatives tend to be very concerned about energy and economic issues, and addressing their concerns can be a productive place to begin a conversation. One can talk about many solutions to climate change without mentioning this polarizing term.

5. Avoid an "us versus them" frame that will brand your message as that of an outsider.

Framing an issue in a way that attacks conservatives will (surprise!) not make conservatives very sympathetic to one's message. So many communications meant to sway people about climate change's causes did not reflect this simple fact. For example, a series of videos[10] from the nonprofit Organizing for Action that tried to spread the message about the overwhelming scientific consensus on climate change framed it as an attack in an ad that went after particular conservative politicians for their stances on climate change. This framing set up the issue as "science versus conservatives," which is exactly the kind of messaging that can lead to polarization. As a result of communications like this, the message about scientific consensus seemed to be branded as a liberal talking point, and the Pew Research poll confirms that liberals and conservatives differ in how they see the scientific consensus on climate change, despite years of communications efforts about the scientific consensus.

6. Do not stoop to the level of the worst communications—and call out peers who are not protecting the forum for civil discourse.

Be an example of the kind of civil discourse you'd like to see in the world. Defend civil discourse from trolls, incivility, name-calling, and partisan divisiveness. Calling out[11] one's peers when they show poor communication or antagonistic approaches on polarized science issues is an important way to promote better civil discourse.

7. Focus on the local scale, not just the national, and take notes from successful bipartisan collaborations.

If we look only at the national arena, the idea that there could be bipartisan agreement on climate change issues still looks far-fetched. But there is hope when one looks at the local level, at least when it comes to planning for the effects of climate change. For example, a group[12] of counties in southeast Florida has one of the most progressive plans[13] for climate change in the nation. Sea level rise, hurricane damage, and flooding in this area are worsening, and the community has to deal with it. Southeast Florida has a progressive plan because both political parties worked together on it. And both parties protected civil discourse around the issue by nipping in the bud any antagonistic partisan talk from their own group that started to get in the way.

8. Emphasize positive social norms.

Some of the people least engaged[14] with the issue of climate change are those who don't hold a strong opinion about it at all. They don't seek out information about it and don't pay much attention to stories about it. These groups can be liberal or conservative. A subset of them, the "cautious," tend to fall in the middle in their cultural orthodoxies and to stick to social norms. Emphasizing that the acceptance of the climate change's cause is widespread and noting social norms associated with this viewpoint may help reach[15] this subset of those who do not readily engage with information about climate change.

9. Make your message entertaining and widely available.

The other subset is the "disengaged," who tend to be of lower socioeconomic status and also tend to feel as if they have more immediate concerns than climate change. To reach these groups[16] and capture their attention, try framing the information in a way that is entertaining (perhaps employing humor or narrative), easy to digest (perhaps using well-designed visuals), and available on the outlets people already tend to watch or read.

10. Use sources and venues trusted by your audience.

In journalistic and documentary stories, it can be helpful to interview or cite sources that your audience is not going to dismiss. There are conservative politicians[17] and industry[18] officials who have said they think climate change is human-caused, and they can serve as sources to back up the science. In addition, paying attention to the ways these sources talk about climate change and what resources they cite can help you think about how to present this information to a more conservative audience. And venue can also matter, meeting the audience on their turf, rather than your own. The Pew Research data repeat what has been shown in other work: Public trust in the media is incredibly low. So, are there media that people do trust? Conservative-leaning news media that score higher[19] on trust than other news media include The Economist and The Wall Street Journal. But to reach the most people—including those with the least engagement that I mentioned in item 7—media channels with broad, mass appeal reach the most people, even if they are not necessarily trusted all that much.

11. Ignore the loud but small fringe groups.

The Pew Research data reinforced previous findings that climate deniers make up an incredibly small portion of the population (about 10 percent). Because climate deniers are so vocal, it can seem as though they are a much larger group. Indeed, the Pew Research poll shows that conservatives tend to think that media coverage of climate change is unbalanced and exaggerates its threat, a testament to climate deniers' messaging. Small fringe groups often use any means necessary to get attention, and the best way to avoid spreading their misinformation is to ignore these attempts. Mentioning misinformed viewpoints that do not stand up to fact-checking lends them undeserved credence and can unwittingly spread them through a much larger audience than a small group of naysayers could garner on its own. Indeed, giving too much airtime to a vocal fringe group that disagreed with the majority view of climate scientists may be one of the reasons[20] that climate change denial reached the proportions it did.

12. Make it clear how small the group of climate deniers is.

If climate deniers are to be mentioned at all, it should be clear that their numbers[21] are minuscule. People are unlikely to jump on a tiny bandwagon.

13. Affirm the intelligence of your audience and whenever possible give them what they really want—to be heard

There is really interesting literature[22] in science education on how to teach science to those who hold conspiracy theories (especially with regard to teaching evolution). People who hold conspiracy theories of any sort, including climate denial, tend to want to feel heard and to be told that they are intelligent and assessing all the information as a good researcher would. This kind of encouragement sometimes can be difficult to navigate in a larger public forum, but it can be especially effective in classrooms, small groups, or one-on-one interactions, where one can continue to encourage a person to assess all the information, including the information with which they disagree.

FOOTNOTES

[1] http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/10/04/public-views-on-climate-change-and-climate-scientists/

[2] http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/

[3] http://www.culturalcognition.net/blog/2014/4/23/what-you-believe-about-climate-change-doesnt-reflect-what-yo.html

[4] http://environment.yale.edu/climate-communication-OFF/files/Six-Americas-September-2012.pdf

[5] http://www.climateaccess.org/sites/default/files/Feygina,%20 Goldsmith,%20&%20Jost_System%20Justification%20and%20Disruption.pdf

[6] http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-012-0513-6

[7] http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1981907

[8] http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v3/n4/full/nclimate1754.html

[9] https://youtu.be/WSB21l4QR_Q

[10] https://youtu.be/uMRVUWZrVjk

[11] https://twitter.com/BrendanNyhan/status/558095308702613505

[12] http://www.southeastfloridaclimatecompact.org/

[13] http://www.southeastfloridaclimatecompact.org//wp-content/uploads/2014/09/regional-climate-action-plan-final-ada-compliant.pdf

[14] http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/

[15] http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/ Global_Warmings_Six_Americas_book_chapter_2014.pdf

[16] http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/ Global_Warmings_Six_Americas_book_chapter_2014.pdf

[17] https://youtu.be/TJcapPimRbg

[18] http://corporate.exxonmobil.com/en/current-issues/climate-policy/climate-perspectives/our-position

[19] http://www.journalism.org/2014/10/21/section-1-media-sources-distinct-favorites-emerge-on-the-left-and-right/#smaller-audience-but-strong-trust

[20] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378003000669

[21] http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/six-americas-2016-election/

[22] http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v4/n4/full/nclimate2143.html

This article was written by Katie L. Burke, Digital Features

editor at

the American Scientist. She holds a Ph.D. in biology and her dissertation research focused on conservation biology and the ecology of forests and plant diseases. She blogs at www.The-UnderStory.com.

The American Scientist is a publication of Sigma Xi,

the Scientific Research Honor Society.

This article appeared October 26, 2016 in American Scientist and is

archived at

https://www.americanscientist.org/blog/from-the-staff/moving-beyond-impasse-in-climate-change-communications.