WHAT HAPPENS WHEN FAMOUS NOVELISTS 'CONFRONT THE OCCUPATION' IN THE WEST BANK

by Mattie Friedman

Last year, the American novelists Michael Chabon, Ayelet Waldman and Dave Eggers led a group of writers to "bear witness" to the crisis in Iraq, confronting the fate of that country during and since the American occupation — the hundreds of thousands of dead, the vanished minorities, the chaos spreading across the region. The resulting anthology adds up to a piercing, introspective look at what it means to be American in the 21st century.

I'm kidding! Reporting on Iraq is bothersome, and so is introspection. Instead, they came to "bear witness" to the crisis in the West Bank and Gaza, where thousands of reporters, nongovernmental organization staffers, activists and diplomats hover around a conflict with a death toll last year that was about a third of the homicide number in Baltimore. It's the kind of Mideast conflagration where writers can sally forth in an air-conditioned bus, safely observe the natives for a few hours and make it back to a nice hotel for drinks.

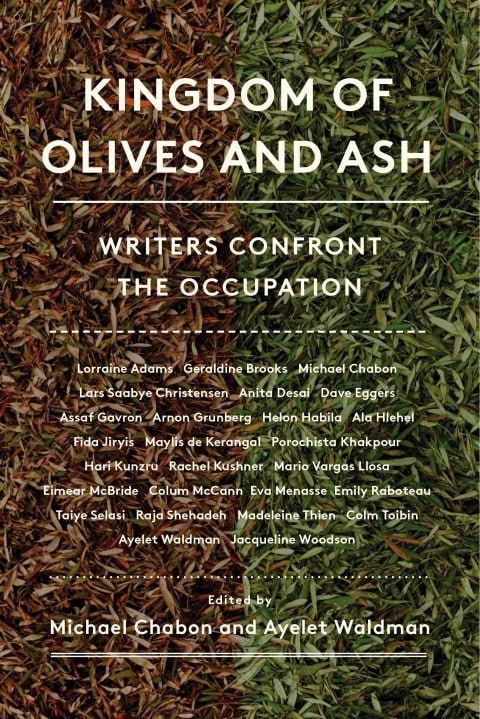

The resulting anthology, Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation, edited by Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman (Harper Perennial, 434 pp. Paperback, $16.99), includes essays by American and international authors such as Eggers, Mario Vargas Llosa, Colum McCann and Colm Toibin — an impressive list — with a few locals thrown in. The visitors were shown around by anti-occupation activists and wrote up their experiences. Edited by Chabon and Waldman, the 26 essays here constitute a chorus of condemnation of Israel.

Chabon, for example, interviews a Palestinian American businessman about life in the West Bank — the byzantine permit system, the 1,001 humiliations of undemocratic rule. Another essay looks at a village of impoverished shepherds, Susiya, in the shadow of an Israeli settlement. Geraldine Brooks describes a stabbing in Jerusalem. We meet children detained by troops, people made to wait at checkpoints and others scarred in different ways by the military occupation that began here after the 1967 war.

I've seen the West Bank from many angles over more than two decades in Israel, as a soldier at checkpoints and as a reporter passing through them with Palestinians, and I know the injustices of the situation are real and worth attention from knowledgeable observers. What we get here, though, is a peculiar product. The visiting writers aren't experts — most seem to have been here for only a few days, and some appear quite lost.

Chabon and Waldman tell us on the very first page of a visit to Israel in 1992, which they remember vividly as a time of optimism, when the "Oslo accords were fresh and untested." But their memory must be playing tricks, because the Oslo accords happened in the fall of 1993. Chabon and Waldman, who live in Berkeley, Calif., are accomplished writers, but the reader needs a few words about what they're up to here. Do they have special expertise to offer? Israel is probably the biggest international news story over the past 50 years, so is there a reason they decided the world needs to know more about it and not, say, Kandahar, Guantanamo, Congo or Baltimore?

The essays vary in tone and quality, but experienced journalists covering the Israel/Palestine story will recognize the usual impressions of reporters fresh from the airport. Cute Palestinian kids touched my hair! Beautiful tea glasses! I saw a gun! I lost my luggage, and that seems symbolic! Arabs do hip-hop! The soldiers are so young and rude! The writers interview the same people who are always interviewed in the West Bank, thinking it's all new, and believe what they're told. Chabon, for example, waxes sarcastic that in the West Bank you can spend months in administrative detention if you forget your ID card at home. But that isn't true.

Everything is described with a gravitas suggesting that the writers haven't spent much time outside the world's safer corners. Eggers devotes two whole pages to an incident on the Gaza border, where one Israeli guard said he couldn't pass and then a different one came and let him through. Dave, if you're reading this, I hope you're okay.

We aren't told, curiously, who paid for this project. But we learn that it was organized by a group called Breaking the Silence, one of many NGOs funded by Europeans and Americans to critique Israeli policy. These particular activists' line is that they're "Israeli veterans," which Israelis know not to take seriously — we have a compulsory draft, and most Israelis are veterans. But it impresses foreigners. The hosts' choreography becomes evident the more you read, because the writers keep going back to the same street in Hebron, the same village near the same settlement, the same checkpoint activist. They avoid Palestinian extremists and average Israelis, so it looks like all Palestinians are reasonable and all Israelis aren't.

We get comparisons to American racism and to South African racism, learn that Israelis don't use water cannons because they're "not cruel enough," and hear Zionism described as "a settler ideology with prominent colonial features under the cover of the Torah narrative." We learn from Vargas Llosa that a small number of Israeli Jews are "righteous," which he thinks is an old feature of Jewish life. The rest of us, apparently, are "blinded by propaganda, passion, or ignorance." Jews reading this might wonder how they became characters in a morality play by Vargas Llosa, but we needn't worry — his criticism is "an act of love."

I know space in these projects is limited, especially with all the love that needs to fit, but the Syrian catastrophe unfolding a 90-minute drive from the West Bank could have used a few more words — half a million people are dead, and millions of others have been displaced. Does this affect the thinking of the Israelis and Palestinians next door? Are Israeli decisions influenced by the bloody outcomes of power vacuums in Sinai, Iraq and Libya? What will replace the occupation? In Gaza, it was Hamas — will it be Hamas in the West Bank? If Israel's police leave East Jerusalem, could the city become Aleppo? These are some of the big questions of 2017.

But the writers here aren't addressing them, which raises another question: What is this book about?

What it's really about is the writers. Most of the essays aren't journalism but a kind of selfie in which the author poses in front of the symbolic moral issue of the time: Here I am at an Israeli checkpoint! Here I am with a shepherd! That's why the very first page of the book finds Chabon and Waldman talking not about the occupation, but about Chabon and Waldman. After a while I felt trapped in a wordy kind of Kardashian Instagram feed, without the self-awareness.

Whatever this anthology set out to be, Kingdom of Olives and Ash is an unintentional group portrait of a certain set of intellectuals. Would they like a curated trip to a foreign country? Sign them up! Do they think a few days is enough to pass judgment on the participants in a century-old conflict? They do! These people are taken somewhere, and they go. Someone points, and they look. They can be trusted not to ask who's pointing, who's with them on the bus or who's paying for the gas.

Once upon a time, in a different America, Mark Twain left on a steamer for a tour of the Holy Land. He had grumpy opinions about foreigners but didn't spare the people with him on board: the pompous, the addled, the hypocrites. He immortalized them in 1869 as The Innocents Abroad. Twain would never have joined anyone's chorus, and we can only imagine what he would have done with the people on this tour — their easily manipulated attention, their blind spots, their belief that they aren't flawed observers of life but a kind of global morality police. But there was no Twain on this bus.

Editor's Addendum:

These are some of the comments that added useful information. We did not include emails that supposedly quoted Jewish leader but were found to be what these days we'd call fake news. Or they cherry-picked phrases that were clearly refuted in context.

Indigenous17 Unfortunately, when it comes to Israel, the left is as blind as the right is to social justice issues. They are so immersed in the narrative and unbelievably biased media, that they simply cannot imagine there is a flaw in the story. The Arabs did one thing right: they figured out how to become the victims and the liberals did the rest. We Jews learned our lesson, World. The old Jewish nebbish stereotype is the opposite of the typical Israeli man (and woman). We will never exploit or oppress; but we won't sit back and be slaughtered anymore. |

|

Kevin Donohue It is not the oppressed turning into the oppressor - it is the almost annihilated learning to defend themselves. |

EvanII Good point! By the way, Mark Twain also accurately portrayed the empty, stateless terrain and populace of the region in the late 1800s -- so grossly misrepresented by fraudulent terrorism apologists today. |

|

Marc J. Rauch The biggest problem with the article above is that it refers to the writers of "Kingdom Of Olives and Ash" as famous novelists. They may be novelists, and they all may have had some success in having their work published, but to refer to them as famous gives them far more "gravitas" than they (and their opinions ) deserve. And when you especially consider that their opinions are wrong (yes, an opinion can be right or wrong, not just neutral because they're personal opinions), why give them any credibility at all. The writer of the article, Matti Friedman, treats us to his view that "injustices of the situation are real and worth attention from knowledgeable observers." I understand that he's anti the message of the book in question, but it's not necessary to know his wrong opinion, even if he's anti the book. There are no "injustices of the situation" other than those attributed to Jews wishing to live in safety by a world filled with Jew haters. Returning to the initial point of these writers being famous; even if they were famous, they are novelists. Novelists write fictional stories. Fictional stories are stories that are not true. Ascribing any value to their opinions on the subject of Israel would be like asking Carl Sagan to write a thesis on the quality of life on Krypton before the planet exploded and baby Kal-el was sent to Earth to become Superman/Clark Kent. If you want to read the accounts of famous writers who are not writers of fiction, but fact, then you should read Edwin Black's "Financing The Flames," and Tuvia Tenenbom's "Catch The Jew." The former is a famous investigative journalist who exposes the hypocrisy of the Jew-hating NGOs; and the latter is a satirical current events writer who explores the same hypocrisy with very funny results. |

garybkatz No doubt they define "fanatical Zionist" as someone who is aware there are no "Palestinian" leaders who really want peace and are willing to accept a Jewish state. In other words, a "realist." Perhaps a realist who actually learned something from the 2005 Gaza pullout, and its disastrous aftermath. |

|

Imagemaker Chabon and Company chose to ignore that this dispute is and always was over the legitimacy and permanence of the State of Israel in the region. The parties to the dispute are Israel and the Arab states, not Israel and the Palestinians. The crux of the dispute is the continuing refusal of Arab states — the losers of all the wars — to meet the central requirement of U.N. Resolution 242:

|

Serge Roizman The deception that runs throughout the text will bewitch the average reader into believing that the Israelis are usually bad, usually wrong, usually to blame; that the Palestinians are usually good, usually right, usually blameless. And that's what makes this book both shameful and dangerous. For in truth there is no moral equivalence between an army that warns its enemy of an impending attack so that people might have a chance to steer civilians to safety and a terrorist entity that targets unarmed men, women, and children. There can be no rational comparisons between a nation that collectively shuns and condemns those among them who have resorted to violence, and a people that celebrates murderers as martyrs, names town squares in their honor, and pays surviving family members for the barbarity, inciting and incentivizing even more bloodshed. There's one glimmer of hope in the book, in an essay called "Occupied Words," by the Norwegian novelist Lars Saabye Christensen. Christensen reflects on a sad reality: "You can talk matter-of-factly about ISIS...but as soon as you talk about Israel, the tone is different, implacable, loud. Comparisons are made with South Africa. Comparisons are made with the Nazis. Anything can be said about Israel. And there's a lack of proportion or a blind spot, in this increasingly hateful language, in which anti-Semitism appears as a shadow, a trace, a rumor being spread." His fellow essayists in Kingdom of Olives and Ash prove

Christensen right. Even—or maybe especially—in intellectual

circles, anything can be said about Israel. Horrified readers

should break their silence. See the essay

by Daniella Greenbaum, June 14, 2017 at |

|

Charlie-in-NY You need to re-read the review, then. The point is that it does not conform to the reality on the ground but is a cheap form of virtue signaling, and a morally dishonest one at that where other conflicts have taken a far greater toll in life and human misery. But, because those catastrophes involve either Muslim on Muslim or Black on Black violence, and Jews are nowhere in sight, no one cares. Even where Palestinian Arabs are involved, the outrage always ends at Israel's border. If you really cared about them, then why not address their murder in Syria, the actual apartheid conditions in Lebanon, the Arab League resolution from 1959 depriving them of any right to resettle and attain citizenship (beyond Jordan) in any of its member states? And that's just for starters. You need to look in the mirror and ask yourself why that is - if trying to end human suffering, or even just that of Palestinian Arabs, is your true priority. |

robert-2015 US aid to Israel is 2% of Israel's economy, and much of Israel's defense technology is home-grown. So it is silly to claim that Israel's military might is thanks to US taxpayers. And Israel does not play victim, for having a Jewish army to defend the Jewish state means they don't have to be victims. That's kind of the whole point. Matti Friedman does a fair and balanced job here, and he has been consistently brilliant in his writing on the ME. |

|

Robert-2015 The only ethnic cleansing that happened in Israel was in 1948 when the Jordanians conquered Judea-Samaria, renamed it "West Bank", and kicked all the Jews out. Fortunately, 19 years later, Israel liberated it and Jews can live there again. There was quite a lot of additional ethnic cleansing throughout the Arab world at that time as well. About 750,000 Jews had to flee Arab countries. Fortunately, they had Israel to take them in. |

Charlie-in-NY The Arabs conquered the area now held by Israel as part of their 7th century imperial expansion. They are not the indigenous population because the actual indigenous population - the Jewish people - survived, both there and in far greater numbers outside their ancestral homeland. Is there some statute of limitations you use that allows you to include British occupation of Northern Ireland but exclude Arab occupation of the holy land? |

|

Charlie-in-NY Responding to "Concerning the Israeli occupation/apartheid, these words of Michael Chabon, are what stand out for me: "the most grievous injustice I have ever seen in my life". That may well be true, in a very literal sense, as Friedman points out, the Chabons of this world go to Israel for their virtue signaling rather than Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, Congo ... sadly, it's not as if there aren't far greater human catastrophes. Israel is perhaps unique in an important respect: it is the only conflict in which the supposed victims (Palestinian Arabs) in fact hold the keys to their freedom. Peace, however, would require an acknowledgment of History (the Jewish people are the indigenous population), rights for infidels (the Jews right to self-determination in their historical homeland) and justice (Israel comprises 0.25% of the lands surrendered by the Ottoman at the Treaty of Lausanne in 1925, Arabs rule over the other 99.75%). Then, of course, there's that slight theological glitch in which Islam casts Jews as its greatest enemy who are doomed to be a weak and despised minority living at Muslim sufferance until their annihilation in Islamic End Times. |

Matti Friedman is a journalist in Jerusalem and the author, most recently, of "Pumpkinflowers."

This article appeared in the Washington Post on June 23, 2017 and

is archived at

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/what-happens-when-famous-novelists-confront-the-occupation-in-the-west-bank/2017/06/23/4541c1d8-2927-11e7-b605-33413c691853_story.html?utm_term=328131ab79b1